At my current job, during interviews, we like to ask this seemingly innocent question: “What is a good unit test?”.

It turns out that it is a tricky questions. Let’s try to reflect on the practice of testing to make sure that we write our tests as efficiently as possible.

What is a Unit?

Right from the start, we see that the definition of a unit is problematic.

Some people will argue that a unit is a function, a class, or even a package. To me, this feels too restrictive.

For now, let’s define a unit as:

A non-trivial amount of code that does a non-trivial thing

We will see if we can refine this definition as we reflect on the practice of unit-testing.

What is good about tests?

Let’s try to give some properties of “good testing” practices.

Here is what comes through my mind:

- Tests catch when the code breaks in unexpected ways

- They help me design my code while I am writing it

- They give me courage to change/refactor the code down the line

- They provide tight feedback loops

They catch errors

This is the most obvious advantage of writing tests.

Off-by-one errors, typos, or simply a misunderstanding of what the current code does might lead to a logical error.

We are human, we make mistakes.

They help me design my APIs

Through experience, I have become a TDD practitioner. I find that I write code more efficiently when I’m writing a test first.

Following TDD by the book would mean adhering to the Red / Green / Refactor mantra.

- 🔴 Red : You write a failing test that highlights what your code is supposed to do next

- 🟢 Green: You write the minimum amount of code to make that test pass

- 🔵 Refactor: If necessary, you refactor your code (production or test)

=> Repeat until you code does what it is supposed to.

While I find this approach helpful, I do not follow it dogmatically.

What I take issue with is “minimal code to make tests fail or pass”.

If I think a portion of code is getting complicated, I would typically extract a function.

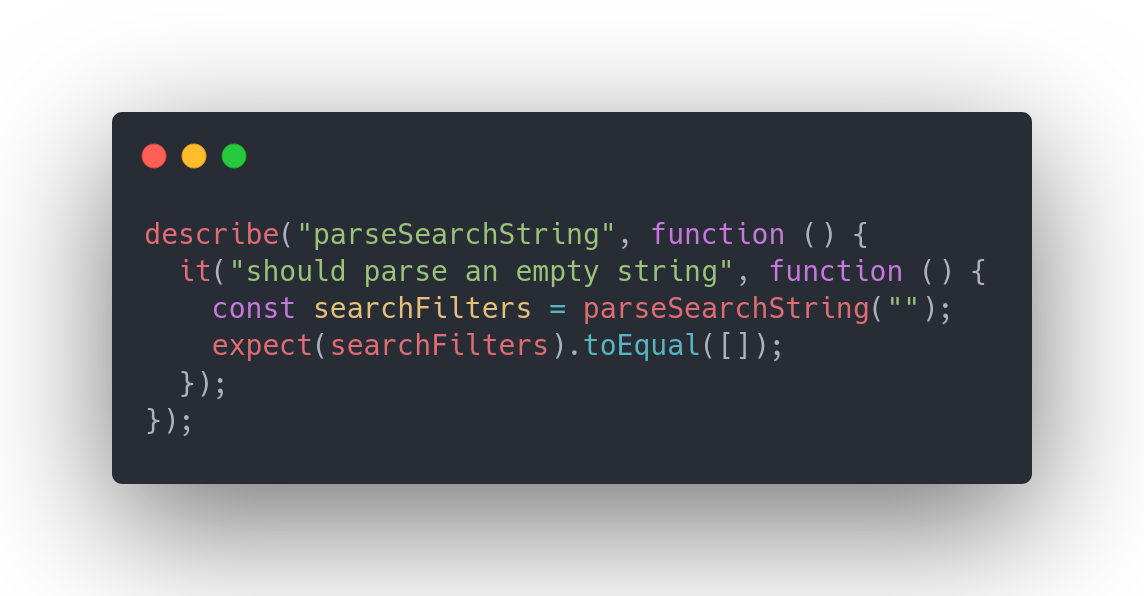

Then, I’ll write a test that looks like this:

test('it works', () => {

const output = myFunction(some, input);

expect(output).toEqual(

// what's the API?

)

})

I make it compile by writing an empty function (that probably returns null).

I begin to write types for inputs and outputs.

I start to think about how different inputs change the output.

And then I start to think about edge cases.

If I come up with multiple things to keep in mind at the same time, I might write another test right away. Then, I try my best to write code that works from the get-go.

Of course, by all means, write simpler test cases first. Then write more complicated ones so complexity becomes easier to tackle.

Don’t be dogmatic, be productive.

They give me courage to change the existing code

We all have heard or lived with technical debt.

Code ages and sometimes it does not age well. We want to be able to refactor it to reflect our current understanding of the domain.

This must be done as often as necessary and, therefore, be as painless as possible.

They give me immediate feedback

Unit tests must be fast to run.

This is why some people oppose them to “integration tests” or “end-to-end tests”.

I would argue that you should thrive to make all kinds of tests fast.

The difference between those three kinds of tests might not be obvious and again, I think it comes down to the definition of “unit”.

Let me propose the following definitions:

Integration tests execute code that is “off unit”.

End-to-end tests are about user interactions. Through the UI we can interact with our product and assert what the UI shows.

I would argue that, more importantly than speed, these kinds of tests differ by the maintenance effort they require.

Most people are familiar with the test pyramid, where the base is wider and composed of unit tests, and the tip is narrower and composed of fewer “high maintenance” tests.

Following this practice you’ll have mostly fast, easy to maintain, tests and a few high-maintenance and potentially slower tests.

Is there such a thing as too many tests?

Yes.

One measure of good code is high cohesion and low coupling.

In other words, maximizing how easy it is to change the code.

Ideally, we want a minimal code change to break a minimal amount of tests.

Therefore, we should apply the same “clean code” principles to the tests as we apply to production code.

We should always Refactor/simplify/delete unnecessary tests.

See: Maximize cohesion Minimize coupling

Can we predict the future?

Now that we talked about cohesion and coupling, we might propose a better definition for a “unit”:

A Unit is an arbitrary amount of related code that we expect to change altogether

All the nuance is in “we expect”. With our current knowledge of the domain, we expect some part of the code to be expended in the future.

We might define some extensions points or make it easy to add behaviors by adding variables in an array, or a configuration file.

If your predictions are wrong, you might have over-engineered your code. Conversely, you might have missed potential abstractions that would have made your code easier to change.

I think the latter is definitely better (YAGNI). If a portion of code is hard to change, we can refactor it until it’s easy to change and then, make the change.

Over-engineering complicates testing.

What to mock/fake/stub?

With a better definition of a “unit”, we may want to explore what should be tested and what should not. And what the real difference between unit and integration tests is.

The usual candidates for mocking are:

- Database queries

- Network in general

- Code not directly under our responsibility

My rule of thumb is:

Mock when it is inconvenient to call “off-unit” code.

Some mocking tools are fragile (using reflection, code instrumentation). They make it easy to couple your mocks to implementation details and are prone to breaking.

Remember that mocking couples the testing code to implementation details.

Favor simplicity. Write your code such as dependencies are hidden behind small interfaces or functions.

Then, they become simple to stub.

Mocking is a balancing act between:

- Maximizing speed

- Minimizing coupling of the test code to implementation details

- Convenience (tooling)

You might find some cases where hitting a real database, for instance, is not that “inconvenient”.

If your unit tests automatically launch a PostgreSQL database in a container in 0.5 seconds, it might be a pretty good tradeoff and reduce the overall amount of tests you write, as well as improve your confidence in your code.

See: Mocks Aren’t Stubs

Conclusion

Code always has good reasons to change.

Rigid definitions are not helpful because they might make us forget the most important: tests are a tool that should make the code easier write and to change.

Keep that goal in mind and you’ll write better code.

What about you? Do you agree with my analysis? How do you test your code?